Fox And Bunny, April 15, 2021

MARY JO MATSUMOTO

https://foxandbunny.net/2021/04/15/a-conversation-with-markus-linnenbrink/

I met Markus Linnenbrink, a German-born Brooklyn-based artist over a decade ago through a mutual friend. We spoke a few weeks ago as his show WEREMBEREVERYONE was opening at Miles McEnery Gallery in New York. His work includes vibrant installations that he pours down buildings and walls (such as his outdoor wall painting at SLS Brickell Hotel and Residences in Miami ) as well as paintings that take the form of three main processes: “drips”, “drills”, and “reverses”. He also makes large-scale sculptures and we dive into all of this and more in the following interview.

Markus Linnenbrink’s work has been acquired by many museums and private collections including the permanent collections of Ministry of Culture, The Hague, The Netherlands; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; San José Museum of Art; Hammer Museum in Los Angeles; and Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College to name a few. No matter what kind of art you enjoy, Markus’ commentary on color, his labor-intensive process and consideraton of how art is best experienced is worth a read.

MJ: It’s been a minute. The last time I saw you I was on my way to Berlin, so that must’ve been 2013. Fast forward eight years later to WEREMEMBEREVERYONE, your fifth show with Miles McEnery Gallery, opening tomorrow. How have you been during this crazy year?

Markus Linnenbrink: It’s been crazy. I had COVID in March last year but I’m getting my second vaccine tomorrow, so things are changing. The art world didn’t die. I survived.

MJ: Wow, I’m glad you’re okay! I’d love to hear your thoughts about the work that’s in the show and your feelings about the past year and how it influenced or affected your work.

GAMELANDTIMECURVE, 2020-2021

Markus Linnenbrink: Well besides the stress that everybody was under and what happened in New York in April when people died like crazy and nobody was on the street and it was really empty and weird–I was able to go to my studio. My assistants weren’t coming in at that time so I was alone in the studio. I moved things around and took the time to clean up and structure a little. Then I just went back into work mode by myself and that was really nice. I have a 3,000 square foot studio, and to just have space and freedom was something that kept me sane. I managed to have my regular routine and at some point, my assistants came back when they felt comfortable enough. After I had COVID it felt safer since I was one person that could not bring the virus in, with as little as we knew back then. I just tried for my own sanity to keep the studio going and to work on the pieces that came up. I have a few pieces like the one big sculpture that was started even before the pandemic. We finished it this last year and it was really work-intense. The title of the show, WEREMEMBEREVERYONE, is a nod to what everybody went through, and also about the community here which doesn’t want to let all the people who passed slip out of our common consciousness.

MJ: I noticed some of the pieces mention America in the title. For example, IWOKEUPINAMERICA and ONLYINAMERICA. Can you talk a little about how or if the pieces relate to politics and what you were thinking?

IWOKEUPINAMERICA, 2021

Markus Linnenbrink: I think my work doesn’t scream politics because it’s colorful and beautiful or whatever, but I think of it as a space where you can let your mind wander and think about stuff. The title connects the work to the time it was made and makes you put the single letters together to the word that they form. It gives you a little bit of work that you can put in the back of your mind when you look at them. The title for IWOKEUPINAMERICA is from a song by Lonnie Holley who’s an amazing musician and artist himself, with relatively late recognition. He has a song called I Woke Up in a Fucked Up America, which is what happens to most people of color every day in a certain way and is something that I thought about, especially with what came last year with the demonstrations after George Floyd. And me being–it’s kind of weird when I call myself an immigrant–but I am an immigrant because I lived in a different country and then became a citizen of this country. I’m thinking about this as a German who has come to the U.S. where this problem of racism and slavery existed and very much is still such a brutal reality. To discover how deeply embedded all of that is in this country over the years I’ve lived here is like wow, ok. This is really the way it is. So that had something to do with my reflection on living in this country. That’s where some of the titles for some of the pieces come from.

MJ: It’s also interesting to be thinking about the layers of meaning in them because the actual form of your work is layered. It’s been said that your work is all about process and how you painted yourself out of the picture. I know you weren’t interested in the Junge Wilde trend, the Berlin neo-expressionist work that was big when you were in art school in Germany. But at the same time, I look at it and I feel like there are things in it I find very emotional. I’m wondering am I reading emotion into this? Is it what I’m bringing to it? Or is it in the work?

Markus Linnenbrink: I think what I want is for the work to not be in your face, this is what you have to read or this is where I’m pushing you, or look how great I am at this. Those are the things I don’t want to happen. What I want to happen is the dialogue between the work that is there and the work that is me putting all the labor into a piece over a certain time that grows into what it is. And you’re right about all these layers, there’s a lot of stuff in there. A lot of action in it is painterly action and so that’s all there to explore as I’m deeply into color. Color creates physical and emotional reactions, it’s a trigger.

Sometimes people tell me, oh your paintings make me so happy. But that’s what the color does. The energy of those colors triggers something in the viewer that can be to the point where it’s euphoric. For example, music can take you to a place where you’re out of your body, you’re grooving in it. It’s what people seek when they go to concerts. It’s this euphoria that you share with other people. And you can get that euphoria out of my work if you want it. But I’m strictly against work that just tells you what to do or makes you feel like oh, I got it. I understand what is encrypted in the art and now that’s solved I can move on.

What I want is more of a lingering process where you can look at it and then leave it behind but later come back and find something else you haven’t really seen in the first sitting. Sometimes, people that own my work tell me, it’s something different every time I look at it. They love the process of being able to go back to the work and read it in a different light, different mood, different circumstances. That makes me very happy because that’s what I really want. I want this kind of really loaded piece that you can interact with. I hope that clarifies for you that there is stuff to dig out and there are definitely emotions to words in the title that the piece can trigger.

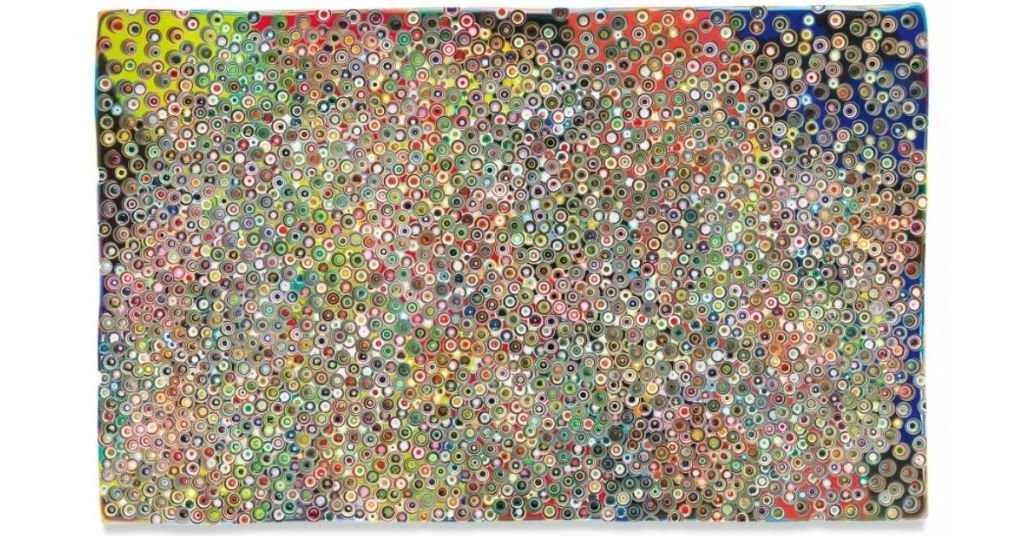

ALONEIWALKEDINRESTLESSSTREETS, 2020

MJ: I feel like there’s almost this jewel-like quality to the drill pieces in your show, that there’s something very dimensional to them. I really like the darkness that comes through and I wanted to ask you about the process for that. I know you’ve said it’s by chance what colors get layered, but is that a decision you are able to control at all?

Markus Linnenbrink: The pieces are all different because there are different colors, different things happening and we push them in certain directions. That’s something you can really only see when you’re in front of the piece. Especially in the last third of the layers, it has a lot of translucency, so the way the light breaks through the layers it’s a whole different story. And that is done on purpose. It’s not like I’m stumbling through the studio and letting things happen.

There are a lot of things that are a little bit by chance but there are ways to control the broadest things. The edges reveal the last layer on top of the painting. If we don’t place the drill holes that closely then you reveal that top layer. If you’re in front of the painting, it’s pretty clear. We layer them until they’re all flat so it’s like a big chunk of painting and then the drilling process starts where we take out pieces. It’s kind of a metaphor of how we deal with time by creating something that is so connected to what happened at what time. That’s what makes them so intricate because every layer happened at a certain time and then the next layer goes on top. And some of the bottom layers of these panels have paint dripped onto the surface by the drip paintings. And the drip paintings–the stripes that run down them are mostly several colors, so the way they drip on the bottom can be revealed in several ways in these drill holes. If we drill less deeply into it a layer of a different time gets shown.

I always say it’s an overabundance of visual information. It’s basically too much to grasp for the human eye. You have to adjust your point of view and the distance of where you’re standing. People will move around in front of the paintings because they want to get a grip on them. You might move closer to see the details and then move out to see the whole.

EXPLAINMYHEART, 2020

MJ: When I was thinking about your process, it seemed like a microcosm for life. I was reading your new publication (which is beautiful by the way) and what Kat Cron wrote in the forward. She says your work is “an investigation into color, material, time, and spontaneity”, and I was wondering if ‘chance’ might also be accurate. Even though you know the steps, it can be different every time, and there’s something almost unknowable about it.

Markus Linnenbrink: Yes, I’m really interested in the moments that just sort of happen, that jump a little bit out of your control. There’s something you have to deal with that was not planned and therefore that’s really interesting. So you go back and look at it and then you decide the next step. It’s a process of letting go and then making decisions again. It’s like what we all have to do in our lives. Sometimes you have to let go of things and then you have to make a decision again and take action. Finding a healthy balance with that in life is like gold. I try to do that in my studio because that’s my life.

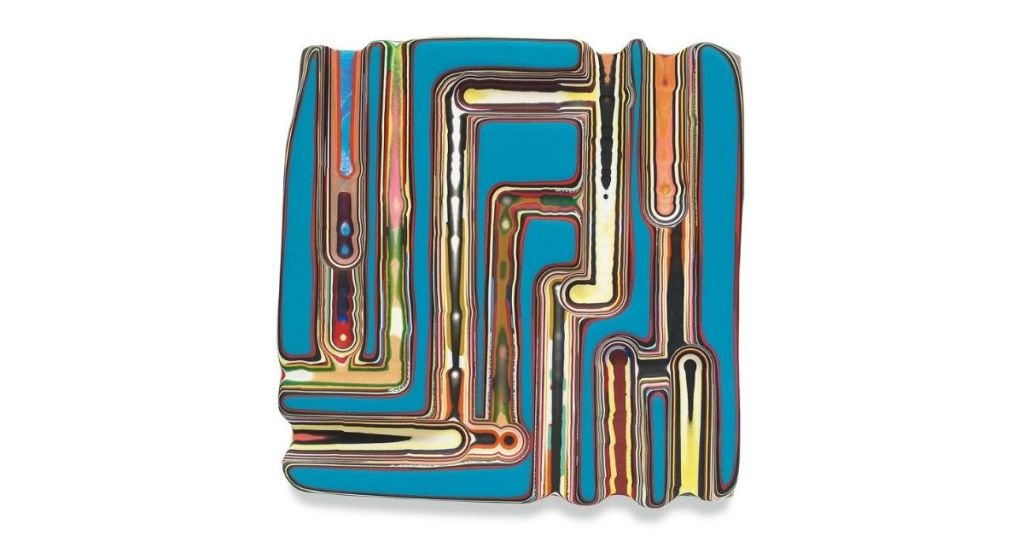

MJ: I really wish I could see these new ones in person, but I will at some point. So the cuts, I think you started doing these around 2015 or so. The little turquoise one DORAMAAR, I think is interesting. They almost look like they’ve been carved into. I think you said you’re using a hand router with an air compressor to do these?

DORAMAAR, 2018

Markus Linnenbrink: Yes, I have a machine that’s basically doing what a CNC machine would do. The CNC machine has a computer-driven router and can create any movement you can program into it. I did a few paintings with a CNC machine where somebody wrote a program and then the machine could do a big painting, 3 x 8 feet, in 20 minutes. It was amazing to watch. I was just standing there and my mind was blown.

But the thing was I had to go to somebody to write the program for me and get somebody to manage the machine. There are too many things where I couldn’t really be involved in the process so I wasn’t one hundred percent satisfied with the result. I also had to invest a lot of handwork to shape the painting the way I wanted it. I wasn’t super excited about the router so I did DELETEYOURSELFRAGE which is similar in style but I did that by hand. Then my carpenter told me he had a similar table that had a router on top that you can control with air. The control is two joysticks. One is for left/right, one is for forward/backward and there’s a foot pedal for up/down. So now the machine I have mimics the same things that a CNC machine would do but in a way slower speed and it doesn’t work as smoothly. It’s like riding a bucking bronco. Sometimes the air pushes too hard or it creates these errors and what you might call ‘mistakes’ that are really interesting for me to work with. I kept exploring the best ways I could use this machine and that’s how all these routed pieces were made in the end.

MJ: Color is such a huge part of your work. I read that when you first started out you were hand grinding your oil paint.

Markus Linnenbrink: Yeah, I was doing that for a long time.

MJ: That’s a labor-intensive process.

Markus Linnenbrink: It is. But it’s also very meditative. I always had this interest in the materials I work with and I always loved to work with pigments instead of pre-bought paints. I did that too but creating the paints that I use out of the dry pigments, which is the origin of every color, really gives you a very intimate relationship to the stuff that you work with. You learn about all the different existing colors and what you can do with them and what works. It’s a field that I really like a lot. I try to use a whole range of colors all the time. But you mentioned DORAMAAR and that’s kind of a blue painting if you want to call it that. And the title is, of course, the name of Picasso’s muse, who I think was underage?

MJ: Sounds about right. I think he physically abused her and emotionally tortured her with his other mistress (Marie Therese Walter) who was underage.

Markus Linnenbrink: Yeah, all kinds of weird Picasso bullshit going on there. So it points to that but it’s also a reflection of how he used the influence of African art to create his distorted or simultaneous look on faces where you see the front and side and different angles at the same time. I titled it after it was done because what we call abstraction is never that abstract because you always find something in it. And if you look at this blue piece, for example, you can see a face in it. Or you can see faces in different ways by looking at it.

MJ: I like that.

Markus Linnenbrink: That’s what I find interesting too. Representational or not, we’re talking about painting and that’s something that’s not pixels on a screen. That’s basically what determines a painting and it’s not about abstract or realism. That’s all somehow obsolete in my mind. I gave up labeling my work because that would just put it in a box. It’s more like having this big canon of what painting can be. I utilize my studio for what interests me without telling myself you can’t do this or you can’t do that. Some things make sense and other things don’t make sense at that moment. But it could also shift to a point where maybe I do want to incorporate wild brushstrokes into my work. Why would I say no to that as a principle? It’s just that I’m not interested in what wild brushstrokes were taken for. If that makes sense.

MJ: Yeah—genius. It does.

Markus Linnenbrink: Exactly.

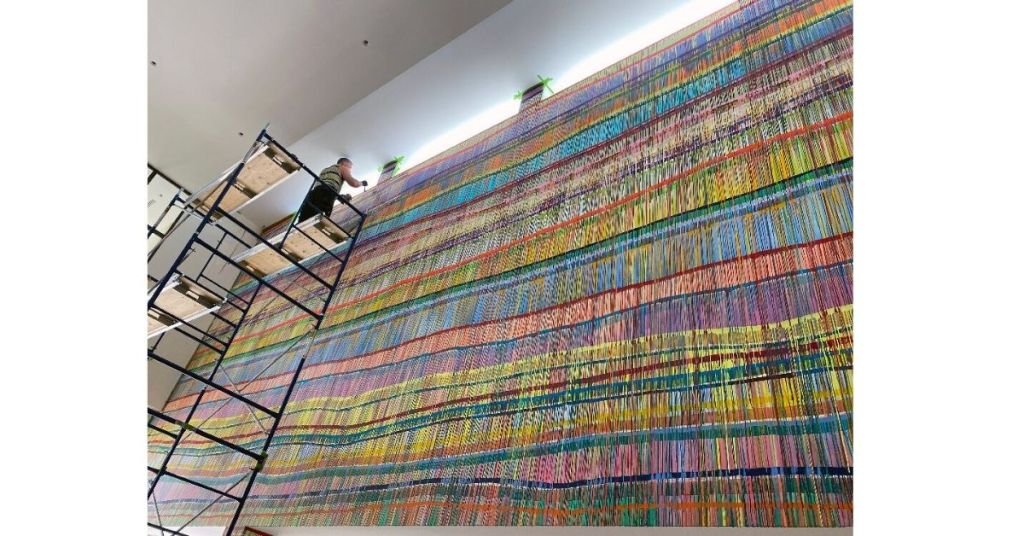

MJ: I thought your works on paper were really interesting and they reminded me of an installation you did. Then I saw that they were done around the same period. I was wondering if they were pieces that you took from the installation.

Markus Linnenbrink, installation

Markus Linnenbrink: Yes, a lot of the works on paper that look like the installation walls are actually made during the time I’m doing those installations. Every color gets mixed on-site and I need to see them dried because I do the walls in matte acrylic. The black and white is Sumi ink, so in order to see that color for real, it has to be dry. I always have a stack of paper with me on site and I create these works on paper using the paint that I need for the walls. The whole piece is only worked this way on-site. It makes the works on paper very specific to the place where I made them and sometimes they’re the only relic that’s leftover when the installation is painted over or gone.

DAYLIGHTTEARSTOMYEYES, 2018

MJ: Can you talk about DAYLIGHTTEARSTOMYEYES and how you created that structure? Something about it sort of reminded me of a Richard Serra structure, but obviously, it’s very different because of the way you handled it.

Markus Linnenbrink: I was thinking about doing a mobile installation piece that also could live in different forms. You can stand it up in a circle, an oval, or in a zigzag and you can face the colors inside or outside. There’s a kind of flexibility to it. I wanted to create this really enclosed endless painting when you’re inside, where the painting surrounds you and you’re really kind of triggered and trapped in there.

I showed it last year in my gallery in New York and we wanted to take it to an art fair, but because of the pandemic that never happened. But the piece is easily dismantled and installed again so it sits in my studio and I can show it somewhere else again. There’s this small opening, you walk in and then you’re just surrounded by the colors inside. It turned out to be a total InstagramVenus flytrap thing. Somebody posted it and then it went viral and all these people would show up dressed up and would walk in and take photos. Not everybody hashtags properly, so there are probably even more photos out there. It was the whole selfie thing and became my Instagram selfie Venus Flytrap, which is also a little bit of a comment on the fact that you almost can’t have a show these days without something that becomes Instagramable. It’s like everything people see has to translate somehow in a good way with them in front of it or has to look good on this three by three-inch square of an iPhone.

THEFIRSTONEISCRAZYANDTHESECONDONEISNUTS, 2015

MJ: You’ve been doing these installations a long time. I was looking at THEFIRSTONEISCRAZYTHESECONDONEISNUTS, which showed in Detroit. It’s almost like a funhouse inside these beautiful wooden structures that are just crazy beautiful.

Markus Linnenbrink: Nick Gelpi, my architect friend in Miami designed the form and it’s basically two mirrored wooden houses on wheels with tiny little cutouts you can look in and out from. He sent me a model of it and I laid out the stripes inside of the model. Then he routed the stripes on the outside of the piece too. It was a really great collaboration piece. You could take this structure because it was on wheels and open it up and we had concerts in there. It was first closed for people to look at, to go inside and be trapped in this room bursting with colors. Then later on during the opening, we just rolled it open so people could fit. And the kids started dancing inside, they had music and a DJ and it became a really nice party like one of those opening days that we’re dreaming of now.

THEFIRSTONEISCRAZYANDTHESECONDONEISNUTS, (Interior), 2015

MJ: Do you want to do more of these installations? How do you see them fitting into your work?

Markus Linnenbrink: I do them when people offer me their walls. I do them as commissions and also like to do them in public spaces. I did a lot in schools and places like that, even for very little money back in Germany. I also liked to do them when they’re shown in the context of not-for-profit institutions. I like the idea that I can create something that is the same for everybody and nobody can say, I’m going to buy this painting and take it home. The experience is very democratic and egalitarian. I like that aspect a lot so when I can take my studio somewhere and do that, I’m always game for that.

DONTWANTTOKNOWDONTWANTTOHEARORUNDERSTAND, 2020

MJ: I saw that you had one of your spheres in the show. Maybe it’s just me and what I’m bringing to it, but I find this very childlike quality to them. I don’t know if you had these in Germany, but I remember super balls growing up. They sold them in gum machines with all these colors swirled in them. When I see your spheres, they always make me smile. Can you tell me more about them?

Markus Linnenbrink: I have one growing in the studio right now. I’ve been doing these sculptures for a long time where I use a plexiform to grow a sculpture inside. The plexi releases the epoxy pretty easily, so you can take them out, and then you have the form without the plexi around it. What happened was that somebody in my studio building was throwing away these two big spheres. I thought why would you throw them away? So I took them upstairs to my studio. They sat there for a while. And then I decided I was going to make a sculpture out of this in the same way I do the rectangular pieces. I distorted the form a little bit because it was not one hundred percent perfect.

ROUNDTHEWORLDANDHOMEAGAINTHATSASAILORSWAY was the first one of these rounds sphere pieces that I did. They had some dents and wobbly parts to it that I really liked. I was like, this is amazing. I need to get some big spheres and keep doing this because of the aspect of playfulness. You have a sculpture that looks like it’s in motion and the idea that you can just set it in motion and push it somewhere or play with it, like with marbles or with rubber balls really triggers childhood memories. The passing of time, who we once were and who we are now, and all these things that you can reflect on by being triggered through the work, it makes a lot of sense to use the spherical form for that. I just really enjoy them.

The sphere is also such a perfect form, it’s mesmerizing in a way. There’s all this stuff that you can discover in it and it tells stories. If you look in the spheres they all have things that I collect, that people give me, that I find. There are trinkets from kid’s toys, old cell phones, and all kinds of stuff. One of the sculptures has a lot of old watches that Ron once gave me. Friends know that I collect stuff like that, so from time to time, I get things. I have a good friend whose mom is always walking around in Brooklyn and she finds the most amazing things that people just drop, from earrings to keys, and all kinds of stuff. The last thing she brought me was a little cross with a metal Jesus on it that’s in this new sculpture.

MJ: Finally, what is your fox and bunny moment?

Markus Linnenbrink: I don’t know if I have that moment concerning my work, because I’ve been painting for 30 years now and it’s been such a nice stream of stuff that happened in the studio. There are people that like my work enough that I can maintain a living from what I do for all these years. That’s kind of magical in a way. I never expected that. And I’m just deeply happy and thankful that people find what I have to say interesting enough and worthy enough to want to live with it or look at it. But there was probably a moment when things got easier after I realized that the only person in my way was myself. That was in my mid-thirties and it had to do with losing one of my balls to testicular cancer. That was an interruption of my life like, oopsie. You try to ignore it at first, but then it’s like, I have to think about this. It made me realize that really, you can’t wait for shit. Whatever it is that you really, really want to do, you have to do it.

MJ: I was looking chronologically at your work going back to around the time Ron (our mutual friend) passed and your work seemed to get darker. I was wondering how much of that was reflected in your work?

Markus Linnenbrink: It definitely had a big influence on my life. He was such a big part of it, you know?

MJ: Yes. This site is dedicated to him.

Markus Linnenbrink: I always had this skull in my studio that was floating around and then Swatch asked me about designing a watch. They allowed me to do a pair of two. One watch has the drip ends of a painting, which is time-related and that watch has a black background underneath the drips. And then I painted this skull I had sitting around in my studio and used the image for the second watch face. I called it TIMEISNEVERTIMEENOUGH. I dedicated it to Ron and he was still alive at that time. It made him happy. After he passed away, I made this whole series of skulls. But at a certain point, I stopped doing them because it was time to let it go. But it was also the idea that every artist should do a skull because–pop culture and everything–but they’re also meaningful beyond that. And they’re part of the whole Dia de los Muertos thing, and that’s a really sweet way to deal with what we all are facing, which is our demise at a certain point.